The Chile cat bond – taking the temperature

Photo: Luciano Queiroz / Shutterstock

The Republic of Chile has just purchased its second World Bank intermediated catastrophe bond. This is the first real test of World Bank intermediated cat bonds in what is currently an expensive market for buyers. As well as adding earthquake protection for Chile’s public finances, this transaction offers useful insights for other countries looking to purchase capital markets risk transfer.

In this insight, Lead Risk Finance Adviser Conor Meenan explores why countries might choose to buy risk transfer even when costs are high and discusses aspects of the bond that affect its final price.

A hot market for risk transfer

Catastrophe (‘cat’) bonds are a risk financing instrument used to transfer risk to the capital markets. They serve a similar purpose to traditional (re)insurance policies but are packaged as securities that are bought and traded among qualified investors.

The full details of the transaction are not yet public, but there are some interesting signals of market conditions based on press releases and news reports. The bond’s risk profile and trigger structure are similar to Chile’s previous cat bond, issued as part of the regional Pacific Alliance bond in 2018. However, the market context is different than in 2018 – for a host of reasons, the cost of buying cat bonds has risen sharply in recent years. This issuance serves as a real-time marker of investor appetite for this type of transaction.

When the Chile cat bond was first offered to the market, it had an initial ‘price guidance’ range of 4.75-5.5%. Once the bids were in, the price settled at the low end of guidance. With a final risk premium of 4.75% and an expected loss of 1%, Chile pays $4.75 in premiums for every $1 they expect to receive in payouts (in shorthand, the risk multiple is 4.75x).

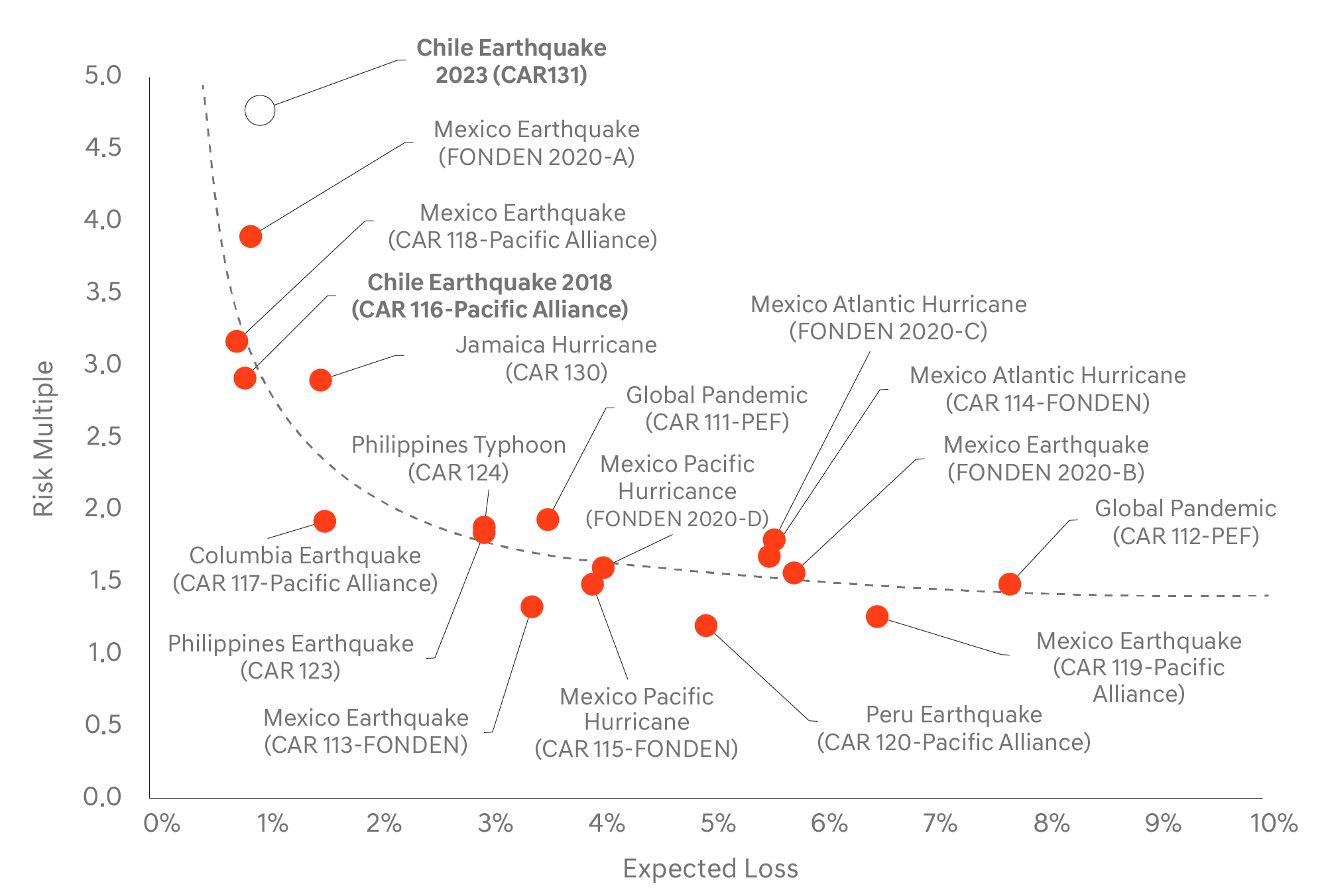

A Centre analysis of historical World Bank cat bonds shows that while the risk multiple of the previous bond was similar to what you might expect based on costs of other bonds issued before 2023 (dashed line), this one is about 60% higher than the historical average for a bond with this risk profile – a sign that the market conditions have changed.

The multiple of 4.75 of the Chile cat bond is the highest ever for a World Bank cat bond.

Source data: Artemis

So, if the cost of risk transfer is high, why would a country purchase $630 million of protection now?

Beyond the numbers – the politics of financial protection

The economic argument that governments shouldn’t need to buy insurance has thawed in recent years, with even the IMF accepting the resilience building role of sovereign insurance. However, even their current analytical frameworks would find a risk multiple of 4.75x difficult to swallow.

Beyond the cold hard economics of a deal, the reality is that strategic, practical, and political considerations also influence financial planning and decision-making. These factors are not always fully represented in the numbers. As with the need to view the cost of a cat bond within current market contexts, the choice to purchase ‘expensive’ risk transfer also needs to be considered with these other real-world considerations.

In the World Bank press release, Mario Marcel, Chile’s Minister of Finance writes:

“This constitutes a new step made by Chile towards a better protected and resilient public finances, in the face of large-scale natural catastrophe events, such as an earthquake, and is part of a comprehensive strategy that reinforces our commitment to fiscal responsibility, which has been highlighted by different local and international agents.”

In this statement, as well as in other presentations and interviews, the Minister of Finance highlights the value of pre-arranged financing to protect public finances against future shocks.

A government can do many things to better prepare for future crises – many of these are intangible, invisible to the public, or are spoken rather than contractual commitments. Buying a big cat bond in a hard market exemplifies that the government is serious about long-term financial planning for potential disasters. This message is important domestically and in terms of international markets’ view of Chile’s resilience and, therefore, the country’s financial options down the line.

Public commitments like this can also be a way for political leaders to spur better planning and preparedness through the public sector. Telling a line ministry that they need to get ready to spend a chunk of the $630m quickly if a big earthquake strikes and that they will be held accountable for getting the money where it is needed quickly may be a better tactic for political leaders than just asking for ‘more preparedness’. The latter is much more likely to lead to performative preparedness. In some cases, the former can be worth an additional cost.

A window on cat bond cost drivers

Transactions like this can offer a useful window into current market conditions. Three aspects of this deal stand out:

1. Cost. Dollar for dollar, this bond is certainly more expensive than the 2018 policy, but even a multiple of 4.75x is low compared to other cat bonds being issued currently – why?

As with historical World Bank cat bonds, this bond ticks a lot of boxes for capital markets investors, which collectively push down the price of issuances like this relative to the average cat bond:

The trigger is a parametric ‘cat-in-a-grid’ structure: Binary payouts of 30%, 70%, or 100% of the limit ($350 million) are calculated based on the reported magnitude of an earthquake, as well as its depth and location in relation to the thresholds set in the pre-defined grid. Investors like simple parametric structures, so the cost is generally lower than for more complex index-linked or indemnity triggers.

Earthquake risk in Chile is ‘non-peak’: Any payouts for Chilean earthquakes are uncorrelated with payouts from other bonds in investor portfolios. This means that this bond is diversifying for investors, which means they can charge less.

The risk profile is remote: The bond has an annual attachment probability of 1.48% (1-in-70) and an expected loss of 1%. The bond provides Chile with tail-risk coverage, and other budgetary and reserve mechanisms provide protection against less severe and higher likelihood events. The remote risk profile is attractive to investors, especially under current hard market conditions.

The bond meets ESG objectives: The way money is managed and spent in World Bank-issued catastrophe bonds means investors consider them to support ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) -related outcomes. This is increasingly important and likely to drive demand from investors with ESG strategies.

2. Upsizing. Chile first tested the market with a $150 million target coverage but has ended up buying $350 million on seeing the investor appetite for this bond. This significant upsize indicates Chile was willing and able to buy more coverage, and plenty of investors were ready to invest at the lower end of price guidance.

3. Swaps, options, and flexibility. As well as the catastrophe bond, Chile has also purchased $280 million of ‘catastrophe swaps,’ bringing the combined coverage amount to $630 million. Cat swaps are a different financial instrument that can be offered to both (re)insurance and capital markets.

Simultaneously approaching two markets has likely generated useful price tension for Chile – allowing them to buy the best average price across two markets, and access a deeper pool of capital to fund the large total coverage. This sort of optionality is valuable for buyers.

A layer of protection plus a strategic lever

Undoubtedly the cost of this catastrophe bond is higher than it would have been over the preceding decade. However, deals like this need to be viewed within the context of current market conditions and considering less tangible government aims. This bond provides a thermometer for both.